In the hills above Quito you can descend into a world of suffering and oppression. From outside the perfect square building clad with dark grey stones looks like a crematorium. Only the smoke is missing from the conic-shaped chimney that punctuates the center of the building. And if smoke were coming from the building, it would have been an offer of peace. Because Oswaldo Guayasamin, Ecuador’s most famous painter, intended his masterpiece to be an ensemble of reconciliation. To not only show the cruelty of people, but also the good sides of humanity.

How the dozens of artworks inside the Capilla del Hombre can be interpreted positively, is still a riddle. Once you descend the stairs towards the granite block, which looks like an impenetrable bunker, only one massive door offers you an entrance. Even that massive wooden gate though dwarfs under the physical and psychological weight of the building. It feels like entering a vulture’s lair. Or, more fitting, the darker sides of the human soul.

When traveling, I can’t help but keep visiting museums and art installations. Because relevant art provides us with views we didn’t see or hear or feel before, asks questions we maybe don’t want to be confronted with, shows us the things we would love to turn our eyes away from.

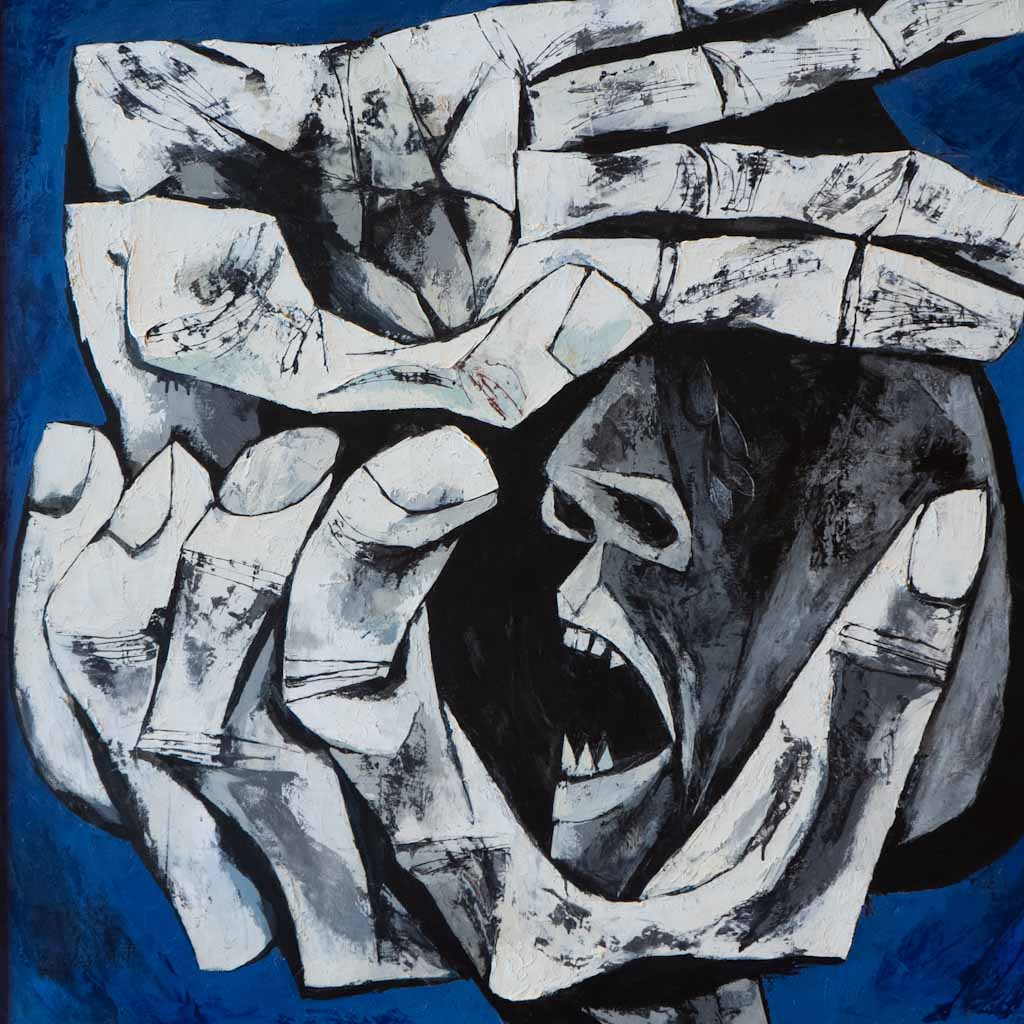

All that is achieved by Guayasamin. Not that his paintings are aesthetically unattractive. It is just that his poignant style, with facial expressions of pain and suffering illustrated mainly in broad strokes on the black-and-white scale, thus almost devoid of color, are like deep views into the darker sides of the human soul. And what men are capable of.

The Ecuadorian artist lived and worked in the adjacent villa, on top of the hills of Quito. His ashes are even buried there under the Tree of Life, in the courtyard. In his workshop are photos with an endless array of world leaders, including of a visit by Fidel Castro, whose socialist policies were fanatically supported by Guayasamin.

But for some reason his fame never really went beyond the Latin American world. Maybe because his work is too dark to be appealing to a larger crowd. Maybe because the general theme of his work was too specifically Latin. Guayasamin, son of an indigenous (Quechua) father and a mestizo (mixed-race) mother, early on in his career embraced the style of Indigenism. It’s a Panamerican movement to denounce the exploitation of indigenous people. And he never really strayed far away from that topic, though he did develop his own style.

My first reference though, upon invading the Capilla del Hombre, was the work of Jose Clemente Orozco. Not surprisingly, the two had met in the 1940s and travelled South America together extensively. Orozco’s most famous works I had seen the previous year in Guadalajara: spectacular murals in vibrant, almost burning, colors, depicting epic battles between good and evil. Dozens of those scenes actually, in the Hospice Cabanas church, including a spectacular painting inside the dome.

The Capilla del Hombre also has a dome, which is painted black on the inside and with dozens of skeletons layered upon each other. There is no sign of life here: it looks like Orozco, but without the colors and without the struggle.

There isn’t much more hope coming from the countless other paintings of Guayasamin in this two-layered building as well. He designed it himself, but never saw the final result upon completion in 2002 because he died three years earlier.

But he intended it to be as a positive counterweight to the two earlier main stages of his career: the ‘Camino del Llanto” (The road of tears), which comprises 103 works produced between 1945 and 1955. It is pretty obvious these were heavily influenced by his friend Pablo Picasso and his Guernica masterpiece, though Guayasamin’s style was even more sparse and his impasto lines even thicker. The main theme, not surprisingly, was the suppression of the indigenous. ‘Our continent’s power, and especially that of Ecuador, comes from the Indians. Who continues to be the cement, the structure of our nationality’, he once said.

The second stage was ‘La edad de la ira’ (The age of rage), depicting the destructive 20th century in all its brutality. But just like in all the other stages of his career, he doesn’t depict specific events. Almost all of his paintings focus on individual humans and what the violence and terror inflicts on them.

Once you dive deeper into the belly of the beast, one level lower on the ground floor, there are some paintings of this period. The Playa Giron painting shows three naked, skeletal people suffering. Almost in monochrome of course. In Lagrimas de Sangre (Tears of blood) there is at least some color, symbolizing the blood dripping down. Rios de Sangre, a triptych with a blood-red background, doesn’t offer much more hope. Three agonized torsos with open ribcages are depicted. Arrasamiento is another triptych, with three female faces as an allusion to the people who died during bombings of Hanoi during the Vietnam war.

In that respect, the bar for providing a shimmer of positivity had been set very low by Guayasamin over the decades. The last stage of his career, ‘La edad de la ternura’ (The age of tenderness), was to be more upbeat. The Capilla del Hombre was to be dedicated to it, including its name. And sure enough, on the ground floor the Eternal Flame burns, as a beacon of hope, pointed towards the conic chimney which admits the daylight straight down onto the flame.

But you can’t teach an old dog new tricks. These ought to be expressions of love for his mother and humankind in general. But the opening salvo on the right side is Los Mutilados, at least a work in creamy colors, but its six panels show almost Cubist versions of human skeletons in despair. Guayasamin apparently loved it because it can be interpreted in a million ways, but a positive one is probably not to be found amongst those million.

The most important work on the left side far surpasses its competitor in its darkness. These are fourteen panels, apparently part of the Manos de la Protesta (Hands of Protest) series that comprises 150 works. They all feature black-and-white hands, sometimes with agonized faces perching behind them. Only the background has some color, but in the darkest kind of blue the painter could find. By this time, as a visitor you almost want to pull your ribs from your cage in anguish.

The atmosphere becomes even eerier downstairs. because the main hall is lit with the strange orange flickering light one associates with street lighting. A massive mural is the neighbor of the eternal flame here. It’s called ‘The bull and the condor’, depicting the struggle between the indigenous people (the condor) and their conquerors (the bull). Guayasamin comes full circle, closing the loop to Indigenism that had kickstarted his career in the early 1940s.

But then, by the time one would almost had given up hope, there is this one glimmer. A beautiful and poetic one. At the end of the corridor, there is one white wall with bronze characters glued on it. ‘Mantencan encendida una luz e siempre voy a volver’, it says, a well-known quote from the great old painter. ‘Keep this light on, because I shall certainly come back.’