During every hike there is this point of no return. You’re too far along the road to go back to base. You’re too tired to think clearly. You’re definitely regretting what you are doing. And you are wondering how much longer you can go on before hopefully reaching the destination.

It happened to me after recovering from my cancer treatment and going for an apparently ’easy’ walk in the forests in Eastern Germany close to the Czech border. Where the final ascent to Königstein castle, now a climb I would do in ten minutes, seemed virtually impossible.

It happened to me and my good friend J on our seven-day trek on the West Highland Way in Scotland. We came with a loaded backpack, ready to hand those over to the luggage service that takes your luggage from town to town, only to find out that high season only started a week later and we could hulk those 16 kilos ourselves for 160 kilometres.

And then of course it also happened in Ecuador, during the Quilotoa loop that is not really a loop you could walk, but more about that later. The cruel thing about this place of eery beauty is that you can also drive straight to the volcanic lake, at 3’914 metres, by bus or rented car from Latacunga in ninety minutes. You make your selfie, have a cappuccino with left-stirred soya milk in one of the tourist cafes, maybe exaggerate by doing a four hour walk around the crater and that’s it. Most people obviously skip the latter part and only focus on the selfies, or go down to the lake and enjoy the huge swing there. Yes, a swing.

Another way

But there is, of course, also ANOTHER WAY. The slightly longer, more difficult, but also more beautiful road. The one that indeed provides numerous inexplicably beautiful views of the valley. That’s also the one where, on the third day on what is the final final ascent, you start to wonder why you are doing all this.

The answer of course comes a little bit later. And it would also have been possible to do this trek in the opposite direction, going 800 metres down instead of up in those three days of walking. But then you would start with the highlight and end in a small village with hardly a cappuccino with left-stirred soya milk in sight. It would be like having intercourse and then proceed to the foreplay. Or watching a football match although someone already told you the result in the first minute. So the ANOTHER WAY was of course the only feasible choice to maintain my non-existing street credibility.

Ominous sign

The first ominous sign was the bus ride from Latacunga. Me was already impressed by myself managing to find the proper bus at the proper time, buying a ticket with my Spanish language skills and seeing on my map app we were moving in the direction of Sigchos, the starting point of the hike. It was supposed to be a 90-minute journey. But halfway the bus driver turned left, leaving the comfortable asphalt road behind us.

My assumption was he was going to pick up some passengers in a nearby village. That turned out to be too optimistic, as the halfway decent road turned into a dirt road, passed a small village after half an hour, to then embark on an adventure with endless hairpin turns and beautiful vistas over steep valleys.

Snow-topped Cotopaxi volcano could be seen from afar. That was still the beautiful part. But after around the two-hour mark even the locals in the bus were getting worried. And that’s of course the moment where you should scratch your head as well.

The road got narrower and narrower, leading to screams of fear by the locals (not by me of course) when the driver was trying to manoeuvre his way out of this delicate situation. Obviously the normal main road had been blocked. But this unplanned detour, at least for the passengers, was a bit much to take. Only at the three-hour mark did we reach the hamlet of Isinlivi, what should be the end of the first day of hiking, and I wondered whether for safety reasons I should just disembark because it was getting too late to walk. Thank God I displayed a rare case of courage, stayed in the bus to disembark 45 minutes later in Sigchos.

Sigchos

Let the walking begin! Obviously not without having a look at the cute little central square of Sigchos. My love for these Plaza Centrals has been well-documented. In this ever-faster revolving modern life these places are a rare retreat, where life seems to slow down to a glacial pace. The bench beside me is occupied by a silver-haired woman with beautifully embroidered clothing, green, yellow and red patterns on a black scarved base. I wonder whether she will even leave this place in the next hour, looking straight ahead and ignoring the foreigner on her left side.

Several blog posts had told me the signposting had been vastly improved in the previous years. It obviously didn’t take long to wonder how dramatic the situation must have been before these improvements. It was called ’The Quilotoa Experience’ then, getting lost over and over again. It’s not much better nowadays, with signs showing you the way out of Sigchos but then leaving you in the dark for an hour, to then surprise you in abundance close to the river before disappearing again. The only reliable way to enjoy this wonderful adventure is, unfortunately, to be glued to your digital phone and the mapping application showing you a very accurate itinerary.

Stray dogs

You are warned for stray dogs beforehand, and to take a stick or a rock with you all the time to stay safe just in case. My first encounters with these four-legged friends are after the easy initial descent into the valley, along a meadow filled with horses. The dogs bark but stay at a distance, a pattern to be repeated endlessly over the next days. It thank God never gets threatening and not even close to the horror story of an acquaintance who was severely wounded during a trek in Argentina when attacked by wild dogs.

Instead, there are glimpses of rural Ecuadorian life everywhere. This is so far off-the-beaten track there are hardly any basic services except electricity. Farmers are working the land manually with axes, which makes for another brilliant picture. Shortly before crossing the river, a woman leaves her shed to calm her dogs and greet the foreigner. I see a small cabin outside of the shed that must be the toilet. Hens are roaming around freely, and following (or chasing) me until the footbridge. It’s a spot just made to enjoy for a small break and some food, to get ready for the ascent ahead. And where apparently in normal times there are a lot of hikers on this trek, during a weekday during the pandemic this place is absolutely mine. Actually, the hotel register in the next two days will betray the fact that the previous hikers were two days ahead of me.

Signs of doubt

The first signs of doubts (not regret, my friends) emerge in the next hour. Maybe make that a hour-and-a-half. Because after the initial delight of spotting some black pigs, and seeing beautiful horses in the meadow I have to cross, the camino becomes steeper and steeper. Every step reminds me a guy from the low countries is not made for this. And where the descent from Sigchos made you forget you are hovering around the 3’000 metres-mark and beyond, here every bit slowly starts to hurt.

Every fifty metres or so I need to catch my breath for a minute. A thirty-something farmer and his son are cutting trees a bit further up. My app shows a zigzag going even further up, which turns out to ignore some more zigzags. Shortly before I reach the main dirt road there is an old man with what I assume to be his daughter. They ask me where I am from. They tell me as well there is no virus here thank God and I need not wear my mascarilla here.

Once you reach flatlands you always wonder why previous parts felt so hard. It’s no different here, as the road curves around the hill to reveal the sight of Isinlivi again. My second visit of the day, and one hour before sunset it turns out it was the right decision to not disembark there from the bus. I decide to not take photos of the llamas in the hostal garden now. Instead I jump straight for the suicide shower to get clean.

It’s actually been a long time I saw one of these. In Central America suicide showers are common. It’s only a nickname of course, but the sight of a showerhead connected to electrical wires still sends shivers down the spine. The electricity powers the heating unit inside the showerhead. If you use more water, it will be slightly colder. If you use less, there is a gentle warm stream. Finding the sweet spot is of course the challenge. Without being electrocuted.

Isinlivi

The llamas are still modeling for me in the morning as well. The beauty of sunrise and sunset can hardly be overstated here, as it peeks above the hills in the morning. There is absolutely nothing to do in Isinlivi, so watching the sun come up from the balcony in your fleece jacket is an absolutely stress-free activity.

The hostals here provide three meals a day, which is rather practical as there are no restaurants or other food options here. The lunch package is much-needed as well, as today’s programme is the same as on the previous and following one: hike down the valley, climb back up to a higher point than where you started.

So the easy part again is in the morning, returning to those valley views that should never become normal. Navigation throws up some hurdles here, and a closed fence at a farm forces me into an inconvenient and steep detour through a meadow full of bulls. On the other side of the farm I notice I could have easily have opened the gates and closed them behind me, proving there is always a lightbulb moment even for the brightest minds around.

Another meadow full of bulls is survived as the river streams on your right side. Turns out there are two options to cross the stream, but the second (a pretty solid steel bridge) you will only discover when you have already crossed the first one: a chopped big tree that has been slightly adapted for hikers. On the other side of the stream all of a sudden signposts appear again as well.

Coffee!?

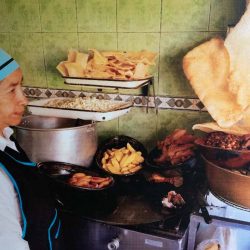

This is as remote as it gets. In the distance a small church becomes visible, but the mapping app also displays a coffee house. Zapallito turns out to be a wooden improvised shed, and one not very much prepared for the odd tourist during a pandemic. A cappuccino with left-stirred soya milk is lightyears away.

Naivity has its advantages though, so I ask the playing kid whether Zapallito has coffee for me. She nods yes, walks to her mother in the garden… and absolutely nothing happens for ten minutes. And as much as I love to chill and be patient, there is still the way up ahead. So no coffee for me.

The church turns out to be part of a village called Ituano. Although it’s not more than a school, maybe four houses and two dogs guarding the sculpture in the center of all of this. If it weren’t for the hungry dogs this would be a good lunch place, so I start the climb up already before recharging the batteries.

This climb isn’t nearly as bad as feared, and definitely easier than the day before. The reward is stunning as well, in the Chinalo village at the top a local farmer was so kind to create a mirador with some benches. After the obligatory Instagram moments local kids beg me. Not for money, but for the food I still have left. There is no saying no to children like this. And the end of the walk is in sight: Chugchilan can be seen around the corner already, though it is still a one hour walk around the valley away.

The Hostal Cloud Forest is obviously built for bigger crowds. Tonight the hammocks are mine and mine only. The lady of the house invites me therefore to family dinner, as there are no guests. The man of the house asks me whether I already tried the local specialty, shots so brimming with alcohol they glide down my throat. A ritual to be repeated obviously in the morning of the farewell, just after breakfast, just after a night where the woolen duvets prove to not be a luxury. We are at over 3’200 metres here and though the sun can be balmy in the afternoons, temperatures often get stuck here at around 15 degrees.

Unknown land

It’s always difficult to embark on journeys into unknown land. Yesterday evening’s vistas were grand, but it was still unclear where the lake of Quilotoa actually was. Turns out the crater mountains were already visible from Chugchilan. It’s deceptively close. Especially because the final ascent is hidden from view.

It starts off easy enough with a descent of course. There are then two options, the shorter and steeper one with a pathway that might be damaged, and a slightly longer one. The latter is my preferred version, and sure enough the first climb to La Moya village is not too easy but also not too hard. Every dwelling in the village seems to have a small outside toilet. Children are playing soccer at the small school, stop and look at the odd passenger and wave, before they continue with more important things. And the sheep in the meadow to the left also don’t seem too motivated to become active today.

The valley views are stunning again. There is though, in contrast to the previous day, a second descent towards a river and accompanying waterfall. And after the walk back up it is slowly dawning on me that all these small climbs are adding up to quite the effort for my delicate beautiful body.

In the next village a signpost appears again that says ’Quilotoa 6.2km’. That can’t be possible, I think with a look at the map app. This one must be the final ascent, It branches off to the left and right, to usually rejoin a little bit later. That takes half an hour before I reach the dirt road. The one of which a blogpost had written it was basically the home straight. What could possibly go wrong?

Long climb

Well, we will never know what would have happened if I would have followed the slowly winding road up the crater. Because my app shows a shorter road, and we are close, right? Overconfidence is man’s worst enemy. We are approaching 3,900 metres and it’s hard to explain what it does to you. But this turns out to be a steep climb. A longer climb than expected as well. And every five metres I need to recover, catch my breath, check my app. This one is slowly killing me, what am I doing here, why the hell did I even start this?

This climb never seems to end. Finally a green sign shows right to Quilotoa. Whether the village or the lake is unclear. Out of nowhere sand dunes appear, as though we are close to a tropical beach. We are not. But what appears around the corner is much more stunning than you could imagine, a view that immediately dissipates all the doubts and regrets that had been lingering only minutes earlier.

In front of me is a perfectly still, clear-blue lake surrounded by rocks and steep mountains. A creation of nature, formed after a massive volcano eruption only 600 years earlier. And when you approach the laguna from this side, the view and the silence are yours and yours alone.

It’s so steep here I initially hardly dare to make pictures, or eat my long-postponed lunch. The sore muscles haven’t dissipated as well, and it’s not clear if and when a bus goes back to Latacunga. So there I go, walking the crater rim up and down, finishing the last two of those 6.2 kilometres to the village of Quilotoa.

This is a different world than Chugchilan, only a short busride away. There are dozens of tourists even on this weekday. Some of them are walking down, which I judge to be one step too far after all these efforts. There are hostals aplenty here, cafes and restaurants, and oh-so-many selfie-takers walking towards the platform for their moment of glory without paying their dues the three days before.

This place feels way too touristy, and I am still in that childish phase of denying I am a tourist. I am a traveler. I do cool things. And it’s time to take the bus to Quilotoa, to finally have a cappuccino again.

(many more pictures of the Quilotoa loop)