Visiting Central America without some knowledge of recent history is like moving around in the dark: you miss a lot of what is going on around you. So here is a short history of El Salvador, with the most important events and their background.

The one essential thing to know to understand El Salvador?

The Civil War between 1980 and 1992. It started with the murder of archbishop Oscar Romero and ended with 75,000 dead people and amnesty for human-rights abusers. Society still wears the scars of those days, and since then El Salvador seems to make two steps forward and one step back.

Alright. But what are the Salvadorans really made of?

Around 10,000 years ago paleo-indian people occupied the lands now known as El Salvador. Maya tribes from the west entered from 2000BC onwards, the Olmecs were the first. The pyramid ruins of Tazumal are a reminder of that heritage.

The inevitable question: how much damage did the Spanish cause during their conquest?

Well, not as much as in other countries, though that is a rather low threshold. Pedro de Alvarado arrived in 1524 and found Pipils in the country, who are descendants from the Toltecs and Aztecs from Mexico.

The Spanish turned El Salvador into a maize-based economy which supported several cities, and around 1700 transformed agriculture to focus on cotton and indigo. But two big problems started to rear their ugly heads: only a small part (14 families) of the population controlled the colony’s wealth, and indigenous people were treated as slaves.

In the end it resulted in the failed 1811 revolt under Padre Jose Delgado. He is still considered the father of independence, as ten years later El Salvador joined the Central American Federation and became totally independent in 1841.

And they were happy ever after?

You’d wish. As the indigo economy turned into a coffee company, the income divide still remained: 95% of El Salvador’s income came from coffee, and two percent of the population controlled the wealth that generated.

Add to that government attempts to stifle workers unions and you see the seeds of the 1932 failed uprising of peasants and indigenous people. La Matanza (The Massacre) left 30,000 protesters dead, amongst them their leader Farabundo Marti. The current left-wing FMLN party is named after him.

So how came the Civil War about?

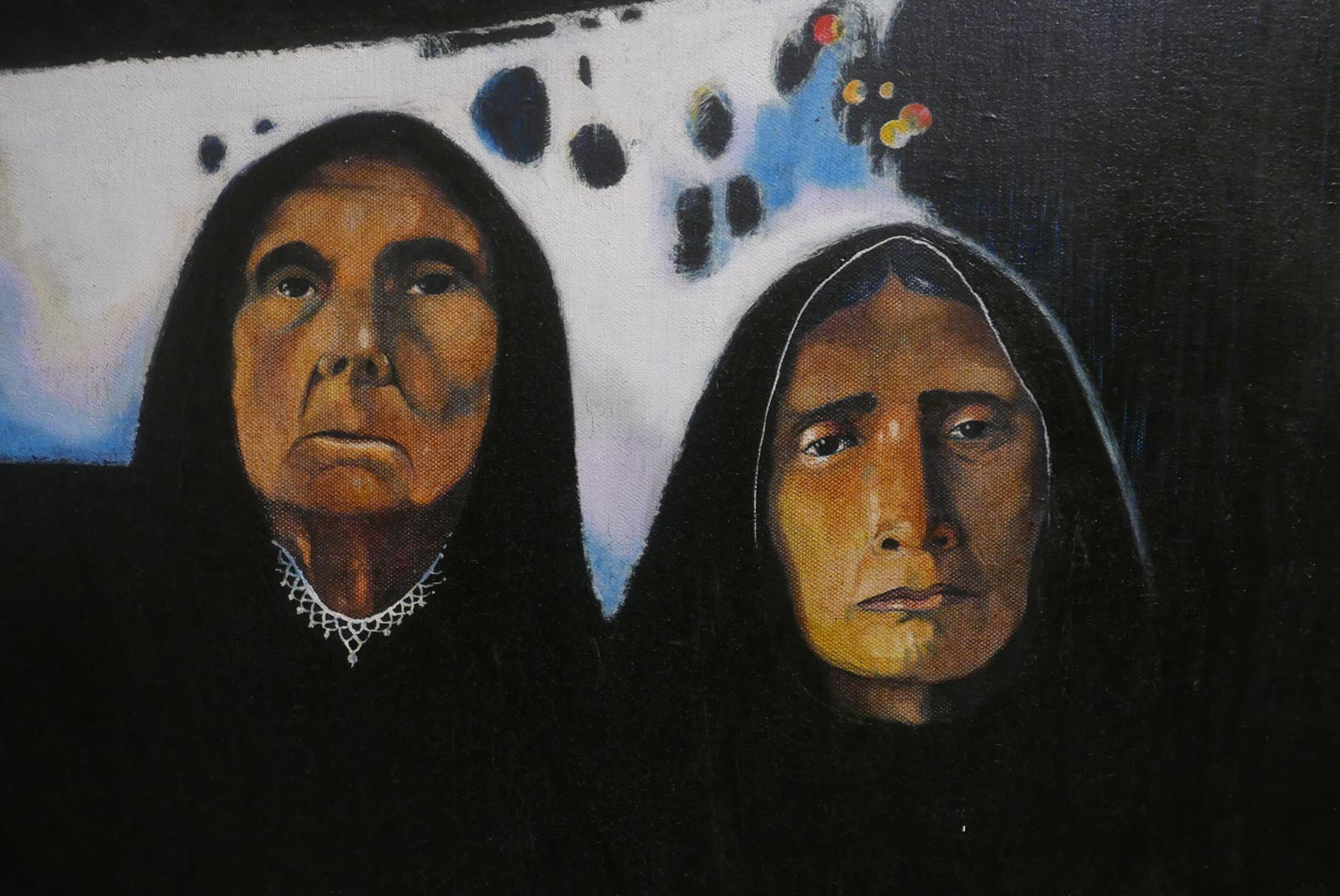

Well, the problems weren’t solved. They actually got worse, because of poverty, unemployment and overpopulation. Political instability (=several coups) were the additional powder in the keg. After an averted coup in 1972, the political right responded to guerrilla activities by sending death squads (and to keep in tune with the title of this blog, that is what the song Mothers Of The Disappeared by U2 was about).

That was only the prelude to 1980. By then, a junta government consisting of military personnel and civilians didn’t deliver on their reform promises. The murder of Oscar Romero, who was on the side of the population, led to the civil war.

Another inevitable question: what was the role of the Americans?

Not a positive one of course. Especially the Reagan government considered the guerrillas to be dangerous socialists, so they pumped lots of money into the Salvadoran army and trained their elite squads. This led to the first wave of killings and a massive stream of refugees.

In 1982 the founder of the extreme-right wing ARENA party created death squads. Several possibilities for peace were missed and subsequently led to a worsening of the violence from both sides. In 1992 a peace deal was finally agreed. The FMLN became a political opposition party. Death squads were dismantled, but there was also amnesty for those who did wrong.

And then they were happily ever after?

At least partially. There were ups and downs, but in general it was perceived as a positive development that the former guerrillas of the FMLN took power in 2009 under Mauricio Funes. They won reelection in 2014 with Salvador Sanchez Ceren. But in 2019, social-media savvy political outsider Nayib Bukele (37) won the vote for a conservative party.

Where are we now?

The votes are still out whether Bukele is an improvement or not. Apart from the still prevailing poverty (one fifth of the GDP comes from Salvadorans living in Amerca), corruption and drug-related violence are two massive unsolved problems in El Salvador’s society.

The corruption is so endemic that entire football teams were suspended, and Bukele could run his platform on anti-corruption messages against his competitors.

The drug violence has its origin in America: two gangs (M-13 and Barrio 18) were formed there in the eighties and nineties by Salvadorans in the USA. They were deported between 2000 and 2004 and started a drug war that has led to extremely high murder rates. It still makes part of San Salvador no-go areas.